In 2018, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia witnessed an unprecedented escalation against women, especially female human rights advocates, where the government launched campaigns of arrests against leaders demanding the elimination of the ban on women driving and the male guardianship system.

Although changes in the system over the last three yearshave restored some rights to women, such as lifting the ban on women driving automobiles and attending soccer matches and once again allowing movie theaters, campaigns of persecution against women have intensified. These campaigns became evident with dozens of arrests targeting women who are then subjected to numerous unprecedented violations in prison, such as sexual harassment, various types of torture, and inhumane treatment. Despite the victims’ confirmation of these violations, the torturers and violators remain immune from punishment. In addition to these violations, the system of guardianship continues to place women under the authority of men in many respects.

Torture and impunity

The documented cases of men and women detainees affirm Saudi Arabia’s use of confessions extracted under torture – during an investigation period that does not allow detainees to avail themselves of a lawyer – as the main evidence to convict them. While the trial cannot be overturned, their trials are sham trials, in violation of Saudi Arabia’s obligations under the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which it ratified in 1997.

In a tweet, the sister of activist Lujain Al-Hathloul confirmed that most of the activists have stated before the judge that they were tortured and sexually harassed by members of the Mabahith (Saudi secret police) before being brought before the court in March 2019 to certify their statements. Despite this, the Saudi Public Prosecutionsubordinate to the king rejectedtheir claims in a hearing held on April 3, 2019, without any transparent investigation.

In chilling confirmation that torture and sexual harassment was covered up and supported by senior officials, Lujain’s sister Alia said the former advisor of the Royal Diwan, Saud al-Qahtani, a relative of Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman, directly supervised a session of torture and sexual harassment against her. Lujain’s sister noted that Saud al-Qahtani threatened to kill her sister, cut up her body, and throw it in the sewer. He also told her that he would rape her before killing her. Saudi Arabia dismissed al-Qahtani after accusations that he was involved in the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi at his country’s consulate in Istanbul on 2 October 2018, but news reports from time to time indicate he continues to maintain his responsibilities in secret.

Despite the many widespread verbal allegations of torture lodged by women activists and detainees, Saudi Arabia has not carried out transparent investigations, in violation of Article 12 of the Convention on Torture: “Each State Party shall ensure that its competent authorities proceed to a prompt and impartial investigation, wherever there is reasonable ground to believe that an act of torture has been committed in any territory under its jurisdiction.”

Oppression’s widening reach

Since King Salman Bin Abdulaziz and his Crown Prince, Mohammad Bin Salman, came to power, the reach of oppression has widened in Saudi Arabia, targeting not only opinion-makers and activists but also their family members should they speak out about the violations inside prisons. The European Saudi Organisation for Human Rights has previously highlighted the violations suffered by the children and families of prisoners of conscience.

For example, in October 2017, Saudi Arabia arrested Al-Abbas al-Maliki after he tweeted the circumstances of the arrest of his father, researcherHassan Farhan al-Maliki. The Public Prosecutionsought the death penalty against the latter because of his religious and historical opinions. Likewise, Khalid al-Ouda was arrested for no stated cause in September 2017, two days after the arrest of his brother, Sheikh Salman al-Ouda, although media outlets said the reason was a tweet he wrote regarding his brother’s arrest.

In addition, the family of activist Lujain Al-Hathloul was threatened after they publicized their daughter’s sufferings in prison: her father was forced to delete a tweet he had written about the situation, and he and several of his family members were forbidden to travel. The pressure and oppression practiced by Saudi Arabia against the families of detainees prevents them from speaking out about the grave abuses inflicted on their relatives in prison.

The serious violations and crimes against oppressed victims, as well as the silence that Saudi Arabia has largely succeeded in imposing, have led some family members to choose to defend their relatives from outside the country. This was the case with Alia and Walid Lujain’s defense oftheir sister, Lujain, as well as Mrs. Maha al-Qahtani’s defense of her husband, human rights defender and member of the HASM Association (Saudi Association for Civil and Political Rights), Mohammad al-Qahtani; Mrs. Malak al-Shahri’s defense of her husband, translator Ayman al-Darisi, detained in April 2019; and Dr. Abdullah al-Ouda’s defense of his father, Sheikh Salman al-Ouda, who was detained in the campaign of September 2017 and for whom the Public Prosecutionsought the death penalty.

Despite carrying out their activities abroad, they are still in danger: they are forced to choose to remain abroad or to seek political asylum to avoid persecution, arrest, or torture if they return to Saudi Arabia. This is in addition to attacks of intimidation and threats of retaliation on social media networks on the part of accounts that are reported to be administered by the Ministry of Interior.

Trajectory of violations

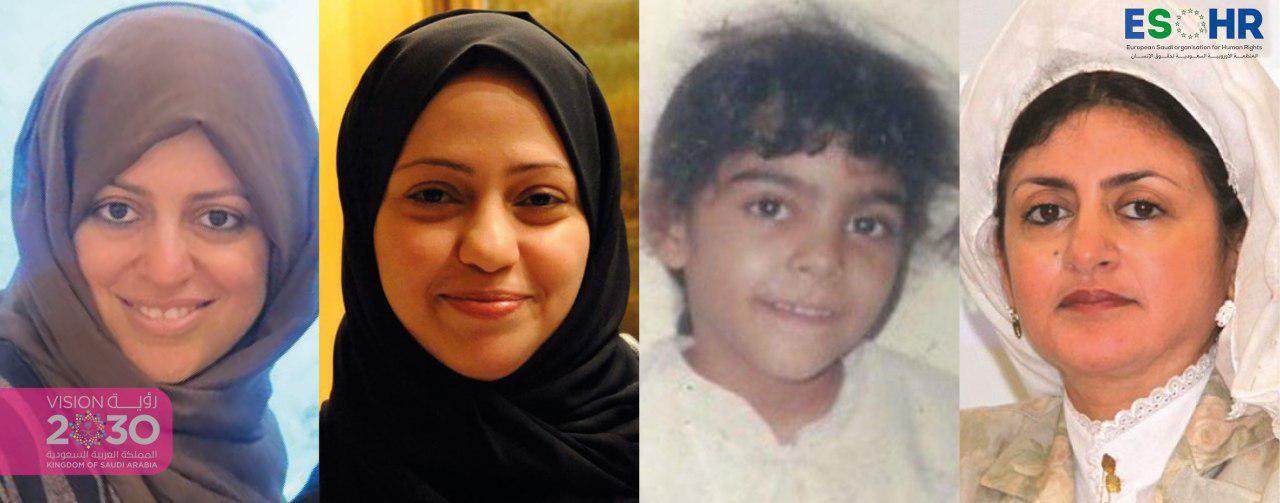

2018 was a year of escalation against women, but it was not the beginning. In 2015, the Saudi government initiated a new phase of targeting, with the arrest of human rights advocate, Israa al-Ghomgham. The Public Prosecutionsought the death penalty for Israa before withdrawing the request under pressure. Currently, al-Ghomgham is still being prosecuted in the Specialized Criminal Court along with her husband and five other activists, as a group. The Public Prosecution continues to seek the death penalty for four of them based on non-violent charges related to exercising their right to freedom of expression: Ahmed al-Matroud, Ali Awishir, Musa al-Hashim (al-Ghomgham’s husband), and Khalid al-Ghanim, along with Mujtaba al-Mazin, for whom the Public Prosecutionsought along jail sentence.

In April 2016, the Saudi government arrested human rights advocate Naima al-Matroud. A year after her arrest, the first sessionsof her trial began in the Specialized Criminal Court in Riyadh, on charges pertaining to participating in demonstrations, photographing of demonstrators, and demanding the release of political detainees. Al-Matroud was sentenced to six years in prison for her peaceful actions.

In 2017, with the ascension of Mohammad Bin Salman to Crown Prince and his numerous promises of reform, particularly in the world media, coinciding with the lifting of the driving ban, the frequency of violations increased. In September, the government carried out a campaign of arbitrary and widespread arrests targeting clerics, businessmen, and men and women activists, including Fatima Al Nasif and Rokaya al-Mohareb.

In 2018, violations reached their peak. In May, a wide-ranging campaign of arrests began, targeting several women leaders of campaigns demanding women’s rights, especially the right to drive, among them Lujain Al-Hathloul, Iman al-Nufjan, and Aziza al-Yusuf. In addition, prominent activists in the field of human and women’s rights were arrested, such as Dr. Mohammad al-Rabia and Dr. Ibrahim Almodaimigh, who was later released in December 2018. Many activists believe that these arrests are retaliation for the role they played in the feminist struggle, in particular those activists demanding that women be allowed to drive and that the system of male guardianship be eliminated.

In April 2018, Saudi Arabia arrested visual artist Noor al-Musallam (19 years old) after questioning her in the Mabahith station on the subject of tweets she wrote in 2015, when she was a minor.

Following that, in June 2018, female human rights defenders like Nouf Bint Abdulaziz and Mayaa al-Zahrani were arrested. In July 2018, the government arrested human rights advocates Nassima al-Sada and Samar Bedawi. The arbitrary arrests were accompanied by numerous violations: detainees were deprived of their right to contact the outside world, and official media outlets proceeded to attack them and level charges of treason against them. Currently, eight of the activists have been freed simultaneously, while others remain under arbitrary detention.

In April 2019, a new campaign of arrests was launched against 15 people, including Dr. Sheikha al-Arf, the wife of lawyer and activist Abdullah al-Shahri who was arrested with her on the same night, and the writer, Mrs. Khadija al-Harbi, in the company of her husband, writer and activist Thamar al-Marzuqi.

Official stance

Since the beginning of the campaign of arrests against women, international voices have been raised, demanding their release and an end to their persecution, including a statement from UN special rapporteurs published in June 2018. In March 2019, 36 countries condemned Saudi Arabia’s practices against women before the Human Rights Council and demanded the release of the activists. In addition, the High Commissioner criticized Saudi Arabia’s practices, regarding them as inconsistent with the promises of reform.

Saudi Arabia has ignored these calls, and has tried to justify the violations, preferring to exert great efforts to mislead international public opinion vis-à-vis its treatment of women, rather than taking true steps toward reform. In an interview with Bloomberg, Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman discussed the existence of audio and video recordings condemning the women.

In addition, Saudi Arabia is trying to burnish the reality of women in the country and appear tolerant by appointing some women to selected positions. Currently, women constitute 20% of the total members of the Saudi Shura Council, all of whose members are appointed by the king. The Shura Council has no real authority – its entire function is to provide recommendations to the Council of Ministers, headed by the king. Likewise, Saudi Arabia inaugurated a nominal division for human rights within the Ministry of Interior, to which Mrs. Ghada al-Brahim was appointed president in March 2019.

On 23 February 2019, a Saudi royal order was issued, appointing Princess Rima Bint Bandar Bin Sultan Al Saud as ambassador to the United States, at the rank of minister. Less than two months after this appointment, 18 American senators, all women, called on the new ambassador to stop the harsh treatment of activists and to immediately release them, as well as to abolish the guardianship system.

After international and media pressure brought to bear on Saudi Arabia regarding its grave abuses of female detainees, the government referred 11 of the activists to the criminal court instead of the terrorism court where many activists are tried. Likewise, on 2 May 2019, Saudi Arabia simultaneously freed five activists – Hatun al-Fassi, Amal al-Harbi, Maysa al-Manea, Abeer Namnakani, and Shaden al-Anzi – following the release of three activists on 28 March 2019 – Aziza al-Yusuf, Iman al-Nafja, and Rokaya al-Mohareb. However, human rights advocate Israa al-Ghomgham remains under trial in the Specialized Criminal Court, along with five men, and human rights advocate Nassima al-Sada has been in solitary confinement since 8 February 2019.

Although there is an attempt to pass off the referralof 11 activists and release of others as a sign that Saudi Arabia has a newfound desire to correct the activist issue, ESOHR believes that this does not reflect reality. The ESOHR stresses that the continued prosecutions, the refusal to drop all charges and immediately and unconditionally release all female detainees, and the lack of accountability for torturers and sexual harassers are proof of Saudi Arabia’s determination to pursue the same repressive approach, with only a superficial process to ease the pressure.

The ESOHR also believes that the violations suffered by women in Saudi Arabia add to the systematic policies of discrimination against women and the continuation of the male guardianship system that restricts women in many aspects. The ESOHR emphasizes that the arbitrary arrests and continuing violations point to the falsity of the calls for reform by the Saudi government, particularly pertaining to women’s rights.

The ESOHR maintains that the release of all women detained arbitrarily, who total 54 according to our statistics, and the guarantee of their right to peaceful, legal action (such as the demand for rights and freedoms) should be accompanied by holding accountable those who perpetrate torture and sexual harassment against female activists. This is the only remedy. Likewise, the ESOHR stresses the importance of eliminating all laws that discriminate against women.